Rewriting the Script of Cancer with CRISPR

By: Sarah Hirji

International School of Tanganyika

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Abstract: Cancer, a complex group of over 100 diseases, arises when mutations in DNA disrupt normal cell division, leading to uncontrolled growth and tumor formation. Traditional treatments like chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery are effective but often harm healthy cells, causing severe side effects. A modern advancement, CRISPR-Cas9, offers a revolutionary approach by precisely editing faulty genes linked to cancer without damaging surrounding healthy tissue. This genome-editing technology holds promise in targeting mutations, especially in blood cancers like leukemia. However, ethical concerns remain, particularly regarding potential germline editing, long-term effects, accessibility, and the risk of misuse for non-therapeutic enhancements. Despite its limitations, CRISPR stands out for its precision and potential to reduce health disparities in cancer treatment. The technology is still undergoing trials, but it presents a hopeful future. With further research and ethical guidelines, CRISPR could transform how we understand and treat cancer, offering personalized and less invasive medical solutions to a historically devastating disease. (ChatGPT, 2025, "Summarize this")

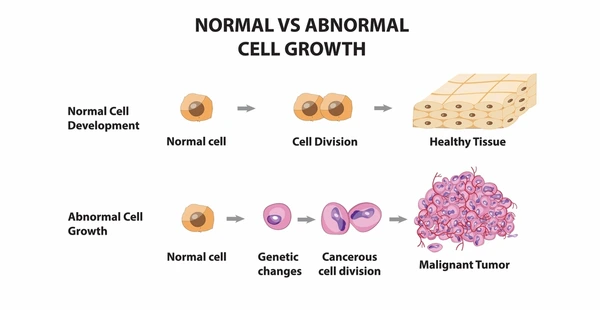

Chances are, you have probably heard the word “cancer” from fundraisers, conversations, or stories from people you care about. But do you know what this word actually means? Cancer isn’t just one disease; it is an umbrella term for over 100 diseases that start similarly (“About Cancer” [00:00:10]). It all begins at a cellular level; every cell is constantly dividing in a process called “mitosis”. Mitosis allows us to grow, heal wounds, and replace old, damaged cells in a usually controlled manner. Cancer occurs when mutations in DNA disrupt the cell cycle, causing cells to divide uncontrollably due to environmental factors called mutagens ("Defining Cancer" [00:00:11]). Mutagens are factors that cause changes, or mutations, in a cell’s DNA. Mutagens can be physical (like UV or X-rays), chemical (such as tobacco smoke), or biological (like viruses such as HPV). When a mutation causes a cell to divide without control, it no longer responds to the body’s signals to stop, resulting in a cluster of abnormal cells known as a tumor.

Figure 1: The difference of growth in normal vs abnormal cells (Normal vs Abnormal)

Two types of tumors exist: benign and malignant. Benign tumors aren’t cancerous and don’t spread aggressively; malignant tumors do, through a process called metastasis. Metastasis occurs when cancer cells travel from the primary tumor through the blood or lymphatic system and form new tumors in distant organs or tissues ("Cell Cycle" [00:05:57]). It is important to understand cancer at a cellular level to be able to understand different treatments.

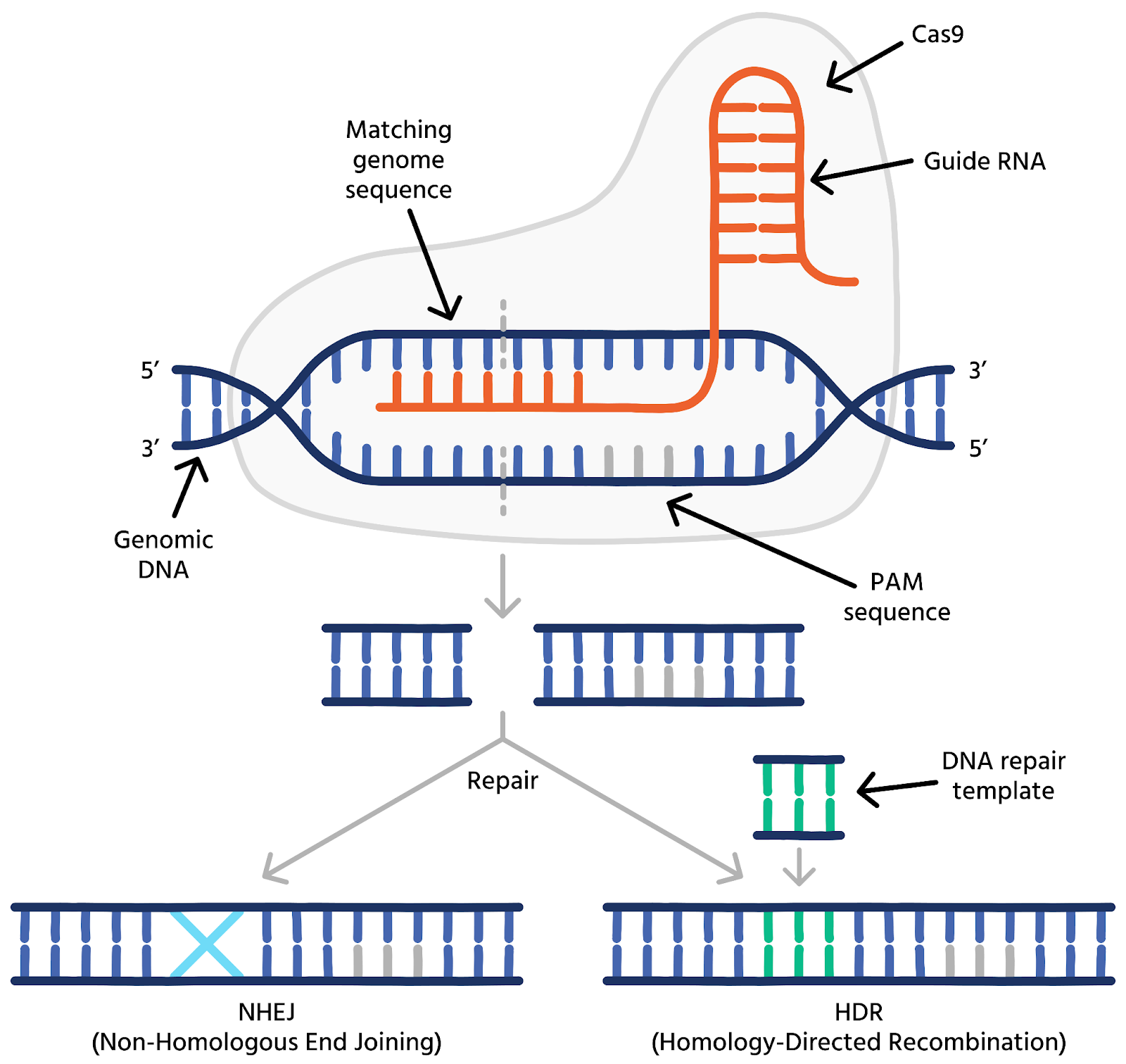

There is no cure for cancer; however, scientists have developed several treatments to combat this disease. Some of these treatments include: chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and surgery. These treatment methods are effective and widely used worldwide; however, most of them come with serious side effects. For example, chemotherapy is a medicine injected or taken orally that kills all rapidly proliferating cells (typically cancerous cells). However, not all fast-dividing cells are cancerous, meaning that chemotherapy could also damage healthy ones. The loss of healthy cells typically leads to hair loss, fatigue, and lower immunity. Additionally, treatments like surgery carry the risk of damaging nearby tissue or causing potential infections (Gersten). Now, imagine how efficient it would be if scientists could find and fix cancer the same way you would find and fix a typo in a Google Doc—by hitting Command F in your DNA code. This is when I introduce you to a modern and newly researched method that does just that: CRISPR. CRISPR, short for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Palindromic Repeats, is a tool used for gene editing that enables scientists to identify, locate, and edit certain parts of our DNA ("CRISPR Explained" [00:00:13]). CRISPR works like genetic scissors and is guided by a protein called Cas9. This protein searches through the genome (which is inside the nucleus of a cell), finds the oncogenic mutation (a mutation that causes cancer), and then cleaves it (cuts the DNA strand) with precision.

Figure 2: CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing mechanism showing how guide RNA leads Cas9 to a specific DNA sequence, which is then cut and repaired ("CRISPR-Cas9 Gene").

There are some advanced cases where Cas9 can replace the damaged DNA with a corrected nucleotide sequence (the building blocks of DNA, like A, T, C, G). This highly specific genome-editing technology can take targeted therapies to a whole new level and reduce overall side effects. Unlike treatments that kill healthy cells as well (chemotherapy), CRISPR can edit only affected genes, leaving everything else unharmed. However, CRISPR is still going through many clinical trials, but it has already proved effective in blood cancers like Leukemia. Scientists are hopeful of its future use in cancer research and treatments (Constantin).

Although CRISPR offers exciting discoveries for cancer research and treatment, ethical factors also play a big role as it develops and becomes popularized. One of the greatest ethical strengths of CRISPR is its immaculate precision; unlike chemotherapy, it only targets faulty genes and avoids unnecessary harm to healthy cells. Additionally, for patients who had genetically driven cancers that would previously be called “incurable”, CRISPR offers a glimmer of hope for a new chance at life. It also supports the growth and advancement of precision medicine, which could explore different ways to personalize medicine that is tailored to one’s genetic makeup. However, this new advancement could raise several significant ethical concerns. Firstly, many could potentially feel like editing a genome is like “playing God”, especially when there is a chance that something could go wrong, and lead to unintended consequences. Even though CRISPR is mainly focused on somatic (body) cells, there is still a risk of germline editing, which means that some changes could potentially be passed down generations. Germline editing is especially controversial because it could cause unpredictable and long term affects on a gene pool which some may view as “morally unacceptable to artificially manipulate the germline as the ‘heritage of humanity’”(Schleidgen). Moreover, there is a risk that some may use CRISPR for non-therapeutic reasons, such as editing traits like height, intelligence, eye color e.t.c. This treatment isn’t always readily available, and it’s resources are limited, which means that those who need CRISPR for cancer treatment should receive priority over those using it for non-therapeutic reasons. Furthermore, although CRISPR is extremely precise, you never know if it may edit the wrong part of the DNA, which may cause future health issues or mutations. Scientists don’t have decades of long-term data as CRISPR was not discovered until 2012 by Jennifer Doudna (Isaacson and Durand 14), which means that it would be difficult to predict long term genetic changes. Not only does the actual process of CRISPR raise concerns, but also it’s limited accessibility. It is a expensive process— around 2.2 million dollars per patient (Rueda), meaning only wealthy individuals and countries will be able to afford it, which increases health inequalities and raises concerns about social justice and equity. Ultimately, as science pushes the limits to what is possible, it is important that we understand to what extent CRISPR is ethical in the use of cancer.

In my opinion, CRISPR has an incredible potential to further advance in the field of medicine. The ability to edit and correct mutations in genes isn’t just a tool for us, but is also a way for us to rethink how we treat diseases such as cancer. While I understand the uncertainty, risks, and costs of this treatment, I strongly beleive that CRISPR should indeed be popularized and researched further. Too many lives have been lost to cancer, and if we already have a tool that is more effective, personalized, and less harmful, I think it is our responsibility to explore it further. CRISPR isn’t perfect yet, but I believe it is a step in the right direction.

Word Count: 1308

Works Cited

"About Cancer | What Is Cancer?" YouTube, uploaded by Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, 26 Sept. 2024, www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Fp83KTFZFI. Accessed 17 Apr. 2025.

"Cell Cycle - Mutagens and Cancer [IB Biology HL]." YouTube, uploaded by Revision Village, 12 Aug. 2024, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qpch7GUFO2s.

Constantin, Laura. "The CRISPR Evolution: It's Transforming Cancer Research, Can It Do the Same for Treatment?" Cancerworld, 1 June 2023, cancerworld.net/the-crispr-revolution-transforming-cancer-research-treatment/#:~:text=Oncogenes%20are%20mutated%20genes%20that,way%20for%20precision%20cancer%20medicine. Accessed 26 Apr. 2025.

"CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Automation." Iota Sciences, iotasciences.com/applications/crispr-cas9/. Accessed 29 Apr. 2025.

"CRISPR Explained." YouTube, uploaded by Mayo Clinic, 24 July 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=UKbrwPL3wXE. Accessed 25 Apr. 2025.

"Defining Cancer: What Is Cancer? Video Series." YouTube, uploaded by National Cancer Institute, 11 July 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=XakRqi6rTXI. Accessed 22 Apr. 2025.

Gersten, Todd. "Cancer Treatments." MedicinePlus, 6 Jan. 2025, medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000901.htm#:~:text=The%20most%20common%20treatments%20are,%2C%20hormonal%20therapy%2C%20and%20others. Accessed 22 Apr. 2025.

Isaacson, Walter, and Sarah Durand. The Code Breaker -- Young Readers Edition : Jennifer Doudna and the Race to Understand Our Genetic Code. Simon & Schuster Australia, 2022.

Normal vs Abnormal Cell Growth. Shutterstock, www.shutterstock.com/image-vector/normal-vs-abnormal-cell-growth-development-2207801345. Accessed 29 Apr. 2025.

Rueda, John. "Affordable Pricing of CRISPR Treatments is a Pressing Ethical Imperative." Mary Ann Liebert Inc. Publishers, 18 Oct. 2024, www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/crispr.2024.0042#:~:text=Abstract,equitable%20access%20and%20global%20health. Accessed 29 Apr. 2025.

Schleidgen, Sebastian. "Human germline editing in the era of CRISPR-Cas: risk and uncertainty, inter-generational responsibility, therapeutic legitimacy." BMC Medical Ethics, 2020, bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-020-00487-1. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

"Summarize this article and create an abstract for a high school newspaper. It should be around 150 words." prompt. ChatGPT, OpenAI, 29 Apr. 2025, chatgpt.com/c/6810b7f9-5a38-800c-852d-8a94a153421b.